A couple of days ago, at 3:30pm, the hottest time of the day, my friend Francisco and I played a match of outdoor tennis for an hour and half, under the unforgiving sun of August and high humidity of Houston.

For the first 30 minutes, I felt great. Then, my legs were not coordinating with my mind. I only won 4 games in 2 sets. But I was proud of myself to be able to survive the heat.

We took breaks and chatted between games. During one of the breaks, while holding his hot iPhone, he shook his head and told me: “You know what, my phone quits working!” Then he read to me the message on his cellphone screen, which said:

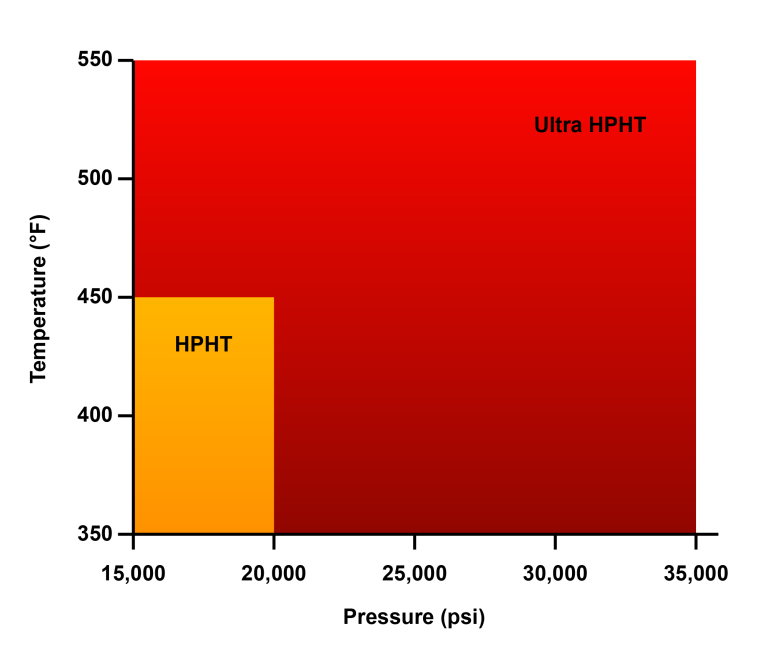

Fig.1: HTHP Classification

We started laughing and felt good about ourselves: we were running directly under the sun and the iPhone was sitting in the shadow of the pavilion.

Heat does amazing things to our bodies, helping us warm up or exhaust us. It was my intention to test the strength of my body when exposed under the sun. It was not my best experience, but it served a purpose.

In petroleum industry, the days of easy, cheap oil are over, making it harder to meet demands without any complicated and expensive projects. As operators continue to drill in deeper and more extreme formations, we are facing extreme temperatures, which create detrimental effects to drilling operations.

More often than not, we encounter high temperature and high pressure (HTHP) conditions, which are defined with the following picture.

HPHT is currently defined as 20,000 psi and 450°F and ultra-HPHT is typically considered anything above.

When drilling a well, we use drill pipes and other tools including downhole motors, which have rubber parts. The combination of high temperature and pressure, and other tough conditions has a dramatic effect on reducing the drilling tools’ ability to withstand the HPHT conditions. When exposed to high temperatures for extended periods, the rubber parts may deteriorate, causing operational failures. High temperatures also have implications for flow assurance (wax, hydrates, or viscosity), stress analysis, drilling tool temperature tolerance, completion fluid density and cementing, etc.

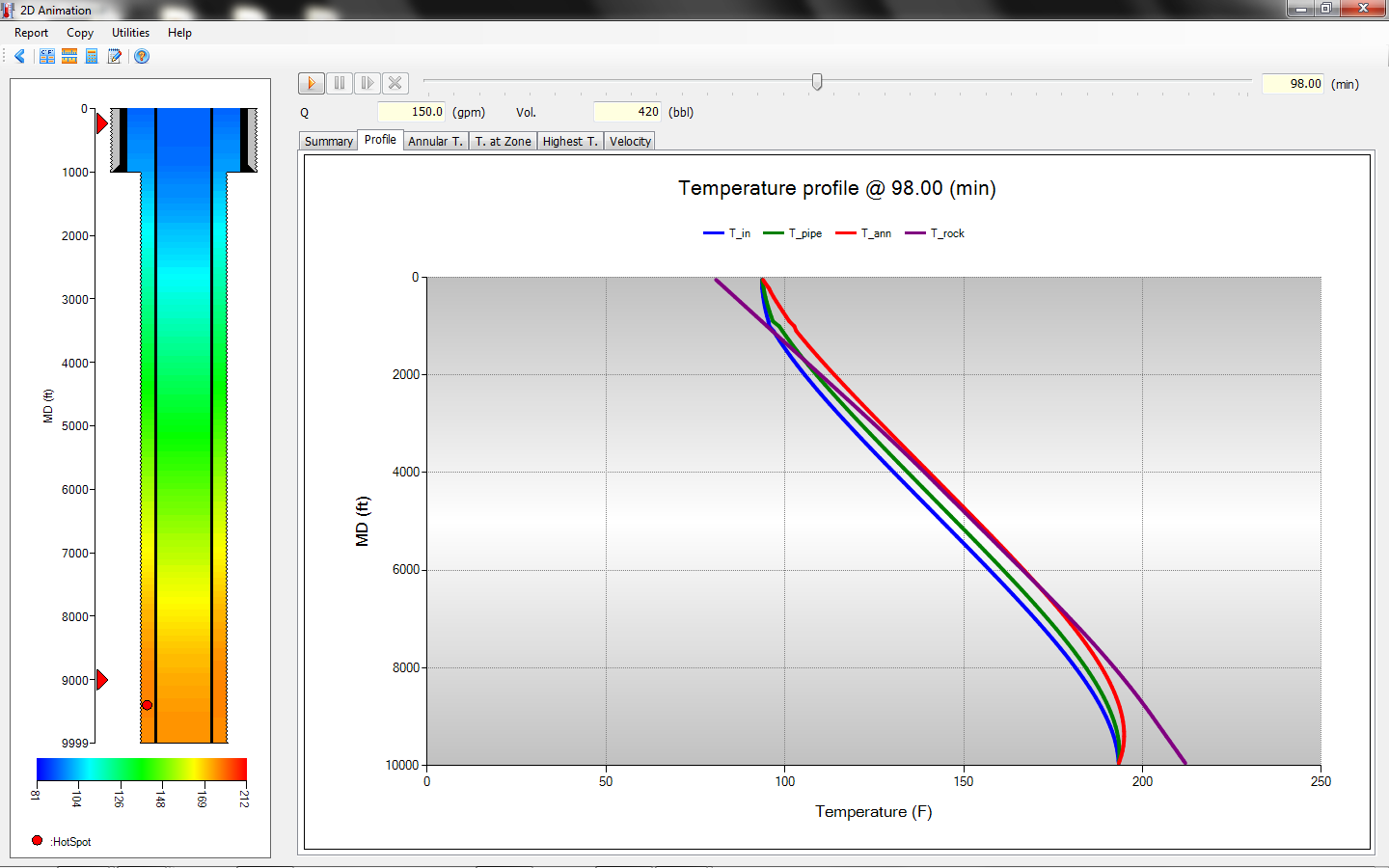

If we can predict downhole temperatures, we can evaluate the risk involved. The downhole temperature changes as we start the mud circulation bring heat from formations at the bottom of the hole upward and release the heat to cool down the formation in the upper section of a well. Here is a snap shot of a temperature profile in a wellbore, using CTEMP, PVI’s Wellbore Circulation Temperature Model.

Predicting the temperature and knowing our limits are necessary for tennis games and drilling operations.